Words by Itziar Burgués & Tara Callahan

Observing cetaceans from land is a more common practice than most people expect or realise. With the right training, focus, patience, an appropriate location and the right information for picking good weather and sea conditions, almost anyone can become an experienced marine fauna observer. The outlet of river Douro in the North of Portugal, for example, is the perfect spot to observe harbour porpoise (phocoena phocoena). It has a long pier at the entrance of the port that enters the sea, giving observers a good viewing platform and is populated by large amounts of foot traffic, especially rod anglers who fish for long hours.

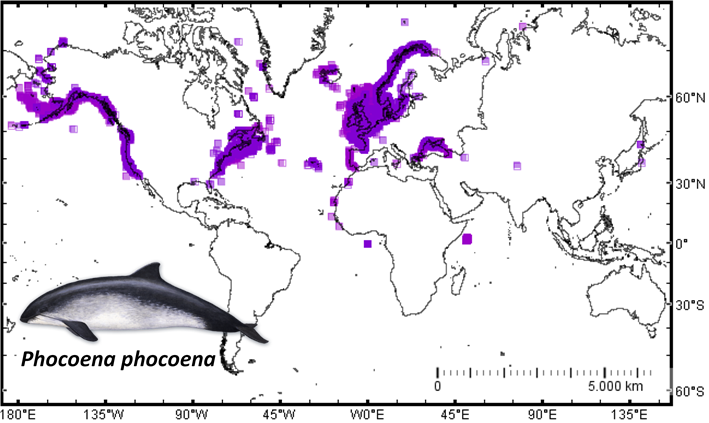

In the summer in 2017, a group of harbour porpoises, including a rare white individual, were observed for the first time from this pier. Since then, a monitoring programme has been enforced in the area to understand more about these animals. Harbour porpoises are often observed from land in productive estuarine areas, where freshwater mixes with the marine environment. Here the porpoises can find attractive conditions for feeding and interacting. The sightings of these animals are countless along the Atlantic and Pacific coasts, as well as at the Mediterranean and Black Seas as their distribution is extensive in the north hemisphere. In addition to the harbour porpoise seen from land at Foz do Douro, common dolphins (Delphinus delphis), bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) and Risso’s dolphins (Grampus griseus) have been spotted in the area during monitoring seasons.

Map of occurrences of harbour porpoises (phocoena phocoena) created with data merged form GBIF.org and ORBIS-Seamap. (see Map citation below for more information on the data).

A structured monitoring program at Foz de Douro (foz meaning river mouth in Portuguese) was included in the CETUS Project from the University of Porto. The CETUS Project is a cetacean monitoring programme built up by volunteers and citizen scientists through their commitment to retrieve good quality data from Portuguese waters. This project does not only operate from land, and includes volunteers surveying aboard on cargo ships operated by Transinsular doing regular routes between continental Portuguese territories and the archipelagos of Madeira and Azores. This volunteer program has thus far helped develop ground-breaking scientific papers on the distribution of cetaceans in the North Atlantic and provided knowledge for the conservation of species that are recognized for protection in international agreements and in Annex IV of the Habitats Directive of the European Union.

Usually, one or two trained observers perform monitoring effort from land when there is favourable weather conditions. In order to assess favourable weather conditions, observers’ eyes are trained to record the wind and swell conditions of the sea, using the Beaufort and Douglas scales. Additional environmental data such as visibility, cloud cover, rain conditions, the number of seagulls present, number of rods being used by anglers and the number and type of boats in the area are collected to help scientists analyse viewing conditions. The presence or absence of cetaceans might be sometimes correlated with these variables. The more anglers there are, the more fish there is and with this it is more likely that porpoise will come to the pier to feed. Also, a flock of seagulls may help to identify where the cetaceans are, as they like to fly above cetaceans and productive feeding zones.

Once the initial environmental conditions have been assessed the fun part begins - the patient testing, sea observation time, looking for any signs of porpoises or cetaceans. At first, the process might seem boring, but the reward of sightings, while enjoying the sea breeze is a pleasant sensation. Sometimes you can spend hour after hour without seeing anything, which is also important, since null or absence data during monitoring also provides clues to habitat usage by different species. Having the animals appear after spending a long time without seeing anything is a wonderful experience. Look! There they are! Over there! I see it! That is why it is important not to despair. The moment you see them, coming to the surface to breathe, in the distance or near by the pier playing with the fish, your breath just stops for a second. That emotion will accompany you during the whole sighting.

Whenever any animals are spotted, binoculars can be used to make a positive identification, and to count the number of individuals - or at least estimate it. Then, tracking them with the naked eye often gives a bigger and better picture of the number of individuals, interactions and animal behaviour. Once five minutes has passed since the last positive sighting of the animals the sighting is considered closed.

Another part of the monitoring includes talking to the anglers at the pier and asking whether they have seen any dolphins or cetaceans in the area. Whilst this information is not verifiable scientific data, it has been valuable in the development of the monitoring project. Starting a conversation with anglers can be as easy as difficult, and there is no protocol to have a successful one. Interesting stories from anglers can help us retrieve more information about the cetaceans. Anglers can be very chatty and fun. They know the white porpoise that lives in these waters quite well, as they have reported seeing it longer that we have records. Anglers say the presence of cetaceans is a good indicator of fish abundance. Some anglers claim to have seen the rare white porpoise with a black calf, which makes us think it can be a female, but we are still working to obtain empirical data to confirm this. Combined with regular monitoring in the summer time, reports form anglers at the pier and sea-users, we have been able to suggest (but not confirm) that a small group of harbour porpoise may have some degree of fidelity to the site at Foz do Douro.

Local knowledge is always to be valued as it often provides hints about what the cetaceans are doing even when scientists have not yet been able to demonstrate what is going on. Such public engagement with sea-farers, anglers and recreational users is important for any monitoring programme so that we can all learn to use and share the marine environment that we depend on.

The white porpoise has been called “Gaspar”, after the popular Portuguese adapted name of the renowned friendly ghost ‘Casper’, who has featured in cartoon series and movies. Worldwide, only 34 records of anomalous white harbour porpoises have been recorded, from which 16 were registered in the Northeast Atlantic Ocean. Gaspar is the first one ever recorded in Iberian Peninsula. The white condition of these animals makes them very visible and can be due to a number of reasons.

Gaspar is one of just 34 white harbour porpoises to have ever been recorded - and the first ever in the Iberian Peninsula. Image credit: Tara Callahan (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)

The difference between albino and leucistic:

Albinism, briefly explained, is defined as a congenital anomaly consisting in a total deficiency of melanin, which is the pigment that gives skin, hair and eyes their colour.The absence of this pigment results in a lack of colour usually in the skin, iris and choroid. A genetic mutation causes the absence of an enzyme (Tyrosinase) that is involved in the synthesis of melanin: no enzyme, no melanin, so animals are usually white with red eyes.

Leucism, on the other hand, is a different condition that has to do with melanocytes - specialized cells that produce and contain melanin, at early stages of the embryonic development. During development, melanocytes normally migrate to the epidermis and hair follicles. When this fails, it results in leucistic animals. The tricky part here is that the melanocytes derive from the same cells that generates other organs and even the central nervous system, and therefore these types of mutations can be linked to neurological effects, problems in hearing and can even cause premature death.

Albino cetaceans are characterized by the total absence of melanin. Therefore, this white individual, Gaspar, is better characterized as leucistic or hypo-pigmented as it still has some black spotting on its upper dorsal side and fin, as well as the animals eyes being reported to have pigment. Although little is known about the albino or leucistic condition in cetaceans, the fact is that the lighter the animals are the more susceptible to predators they might be and also the lack of melanin in the skin increases the probability of sunburns and skin cancer. From the 34 records of anomalous white harbour porpoises, juveniles and adults have been reported so the leucistic condition apparently doesn’t prevent these animals surviving to adulthood.

Gaspar is best characterized as leucistic or hypo-pigmented, not albino, because of the black marking on her/his skin. Image credit: Tara Callahan (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)

Conservation and Data Deficiencies

There are so many questions that remain unanswered regarding Gaspar: is the animal a male or female? How old is the animal? Does it always inhabit the Foz do Douro area? What does it feed on?... These questions do not only apply to Gaspar, but also about the group of black porpoises that are often seen with it in the area. We know very little about these animals and other cetaceans frequenting the coastal waters near to the urban centre of Porto. For the moment, the volunteer team will continue monitoring the presence and behaviour of cetaceans, especially the porpoise, from land trying to understand more about them for management and conservation purposes.

There is an incredible diversity of cetaceans in these waters (more than 27 species have been sighted within the project) but there is also so much knowledge that we don’t have about these animals that is very important for scientists to focus their efforts on them. It is also important to provide the opportunity to citizens to contribute with their observations in a structured way and learn from the encounter experience with such animals. By being a citizen scientist and volunteer, you can contribute to cetacean conservation by helping to fill in data gaps and scientific knowledge, and sharing knowledge and experiences about the cetaceans within the local community. The CETUS project is always receiving volunteers from all around the world for each of its campaigns, and to me being a volunteer this summer season has been a wonderful experience. So, if you’re interested in helping with our research or becoming a volunteer please get in touch – we’d love to hear from you!

Reach out to the CETUS project through their Facebook Page

Find out More

Peer-reviewed publication: Ágatha Gil, Ana M. Correia, and Isabel Sousa-Pinto. (2019) Records of harbour porpoise (Phocoena phocoena) in the mouth of the Douro River (northern Portugal) with presence of an anomalous white individual. Marine Biodiversity Records 12:1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41200-018-0160-3

Map Citations:

GBIF.org (16th July 2019) GBIF Occurrence Download https://doi.org/10.15468/dl.bjc7yb,

OBIS_SEAMAP: Halpin, P.N., A.J. Read, E. Fujioka, B.D. Best, B. Donnelly, L.J. Hazen, C. Kot, K. Urian, E. LaBrecque, A. Dimatteo, J. Cleary, C. Good, L.B. Crowder, and K.D. Hyrenbach. 2009. OBIS-SEAMAP: The world data center for marine mammal, sea bird, and sea turtle distributions. Oceanography 22(2):104-115. http://seamap.env.duke.edu/

About the Authors

Introducing guest contributor Tara Callahan

Introducing guest contributor Itziar Burgués

Hi, I am Itziar! I am a marine scientist interested in marine resources sustainability and in understanding the contribution of healthy oceans to human well-being, topic in which I will be starting PhD very soon. Nevertheless, before decided to go for a PhD I was involved in other marine conservation projects in different locations and I would like to share my stories with you. I am a multidisciplinary and multifaceted scientist, I worked as a research assistant in Chile, I also take jobs as a scientific observer for fisheries, I also love scuba diving and I have participate in several underwater survey campaigns. I am always curious about the oceans!

Hi! My name is Tara and I am an Australian MSc student in the MER+ (Marine Environment & Resources) European program. I am a passionate, caring and worldly science professional with experience and expertise in cetacean conservation, behaviour, distribution and management. My professional interest in dolphins, whales and porpoises began on a conservation, volunteer holiday in Costa Rica in January 2014. After this, I collaborated with the Marine Mammal Foundation, Australia, for my honours research, investigating the social structure, and alliance forming behaviour of Burrunan dolphins (Tursiops australis) in South East Australia. I have been fortunate to live and work with like-minded, hard-working and inspiring people worldwide, including Italy, Ireland, Wales, Scotland, France, Spain and Portugal. Taking the time out to work and travel as a “science nomad” was my best decision, as it is truly an invaluable life and learning experience.

The views and opinions expressed by guest contributors do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Ocean Oculus.