The World Register of Marine Species (WoRMS) has again released its annual list of the top-ten marine species described by researchers during the past year to coincide with World Taxonomist Appreciation Day on March 19th.

Every day in labs, museums, and out on fieldwork, taxonomists are busy collecting, cataloguing, identifying, comparing, describing, and naming species new to science. Some 300 taxonomists globally also contribute their valuable time to keeping the World Register of Marine Species up to date. Today is a chance for us at WoRMS to thank our taxonomic editors for this important task.

We celebrate the work of taxonomists now with the WoRMS list of the top-ten marine species described in 2022 as nominated and voted for by taxonomists, journal editors and WoRMS users!

This top-ten list is just a small highlight of about 2,000 fascinating new marine species discovered every year (there were almost 1,700 marine species described in 2022 and added to WoRMS, including some 300 fossil species).

Fluffy Sponge Crab (Lamarckdromia beagle)

Credit: Colin McLay and Western Australian Museum (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

In 1836, during the second voyage of the HMS Beagle (the ship whose voyage inspired Charles Darwin to synthesize his theory of evolution), Darwin spent eight days in the Albany region of Western Australia, in the vicinity of the type locality of this new species, Mistaken Island. With a scientific name commemorating two key figures of evolutionary biology—the French anatomist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and the HMS Beagle—it’s no surprise that Lamarkdromia beagle is an evolutionary marvel.

The hard shell or carapace of this crab is hidden beneath a fluffy layer of hair-like setae and then further disguised by a chunk of sponge (or colonial ascidian), which the crab plucks and then shapes to fit over its head and back and holds in place with specialized legs. The hairy body and sponge cap make it hard for predators like octopus or fish to distinguish L. beagle from the surrounding sponge and rock rubble habitats in the shallow seas of Western Australia. This tendency to wear a sponge hat is widespread among the larger family of crabs that L. beagle belongs to and explains their common name of “sponge crabs.”

Original source: Mclay, C. L.; Hosie, A. M. (2022). The sponge crabs of Western Australia and the Northwest Shelf with descriptions of new genera and species (Crustacea: Brachyura: Dromiidae). Zootaxa. 5129(3): 301-355., available online at https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.5129.3.1

King Ghidorah's Branching Worm (Ramisyllis kingghidorahi)

Credit: Aguado et al. (2022) (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

When you study branching annelids, it’s not so much opening a can of worms as it is a can of worm. Singular. We have seen a lot of weird animals but branching annelids have got to be some of the strangest. These rare and unusual worms decided that one wormy body just wasn’t enough. The head end starts like a typical worm, but the rest of the body occasionally divides so eventually each worm has a highly branched body with each branch ending in a separate anus. One head, many butts. This species is named after King Ghidorah, the three-headed and two-tailed monster enemy of Godzilla.

While there are more than 20,000 species of annelid worms, this is only the third species of branching annelid to be discovered. All three species are found living inside sponges. It is not clear exactly what they are doing inside their sponge hosts. No sponge tissue was ever seen in the transparent bodies of these worms, and no sponge DNA was found inside them either. It may be that they are only hiding inside sponges and feeding on small particles. Interestingly, while branching annelids have only one mouth, the anuses are specialized. They have many cilia, specialized structures for transporting substances, and in addition to transporting the obvious, scientists think these worms might be able to breathe or even feed with their butts. As crazy as that might sound, branching annelids wouldn’t be the first. Other animals like sea cucumbers and even hibernating pond turtles can breathe with their anus.

Original source: Aguado, M. T.; Ponz-Segrelles, G.; Glasby, C. J.; Ribeiro, R. P.; Nakamura, M.; Oguchi, K.; Omori, A.; Kohtsuka, H.; Fischer, C.; Ise, Y.; Jimi, N.; Miura, T. (2022). Ramisyllis kingghidorahi n. sp., a new branching annelid from Japan. Organisms Diversity & Evolution. 22(2): 377-405., available online at https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs13127-021-00538-4

Demian Koop's Yoda Acorn Worm (Yoda demiankoopi)

Credit: Schmidt Ocean Institute (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Named after two other entities this new species is—and one of them is Yoda! This odd, deep-sea animal is a type of acorn worm. Acorn worms live above or buried in the sea floor, where they feed on sediment or particles that settle on their bodies. They range in size from just 1 millimeter to over 2 meters long. Even though they don’t look like it, acorn worms are some of our closest invertebrate relatives! Hemichordates split off from the ancestors of vertebrates, including humans, 500 million years ago—our evolutionary relationship to these worms is still strikingly evident in our genome and in the gill slits that we temporarily possess as embryos.

New and unusual species of deep-sea acorn worms are being discovered thanks to ROVs, remotely operated underwater vehicles. The genus Yoda was first described in 2012, and earned its name from their long lip-like structures that resemble the long ears of Yoda, the Star Wars character. This species is also unusual in that it has both male and female reproductive organs, but perhaps even odder, only one set of reproductive organs functions at a time. The animal will sometimes breed as a male and other times as a female, a process known as sequential hermaphroditism. This species was named “demiankoopi” in honor of Demian Koop, an Australian developmental biologist who passed away, far too young, in 2021. In the words of the Jedi master: many new discoveries in the deep sea there are.

Original source: Holland, N. D.; Hiley, A. S.; Rouse, G. W. (2022). A new species of deep‐sea torquaratorid enteropneust (Hemichordata): A sequential hermaphrodite with exceptionally wide lips. Invertebrate Biology. 141(3)., available online at https://doi.org/10.1111/ivb.12379

Japanese Retweet Mite (Ameronothrus retweet)

Credit: Pfingstl et al. (2022) (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Last year the Top-10 New Marine Species of 2021 included the Japanese Twitter Mite Ameronothrus twitter. In true Twitter fashion, that was soon followed up with tweets that led to the discovery of another new species: Ameronothrus retweet. Here is the story:

Last year, Ameronothrus twitter was discovered when a photographer posted photos of it on Twitter and a Japanese scientist that studies mites recognized it as a new species. The two teamed up to collect and describe Ameronothrus twitter. That species received quite a lot of attention, and soon another photographer on twitter shared photos of a Japanese mites asking “Is this mite A. twitter?” It turns out it was not—it was a second new species! Since the photographs were taken on the coast of the Sea of Japan, where no Ameronothrus had been found before, they caught the attention the mite scientists. Mites collected by the photographer were found to be a new species that were described this year by a team consisting of scientists and the photographer. They named the mite Ameronothrus retweet in reference to its discovery on Twitter.

In their paper, the team notes that “involving the public in biodiversity research can speed up the discovery of new species and raise the awareness for the yet unknown biodiversity and its protection. It shows the possibility and hopes that the citizen can contribute to zoological taxonomy through frequent communication via [social media], in the same way that new stars are discovered in astronomy.” We agree and are excited to witness the new discoveries that can be fueled by broader participation in science!

Original source: Pfingstl, T.; Hiruta, S. F.; Bardel-Kahr, I.; Obae, Y.; Shimano, S. (2022). Another mite species discovered via social media - Ameronothrus retweet sp. nov. (Acari, Oribatida) from Japanese coasts, exhibiting an interesting sexual dimorphism. International Journal of Acarology. 48(4-5): 348-358., available online at https://doi.org/10.1080/01647954.2022.2074538

Golden Cloak Anemone (Stylobates calcifer)

Credit: Yoshikawa et al. (2022) (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The Golden Cloak Anemone Stylobates calcifer forms a living shell atop its hermit crab host. The intricate symbiosis between these animals solves an ecological problem of life in the deep sea: the pressure and chemistry of the deep ocean make it hard for animals like snails to secrete large shells and so make it hard for animals like hermit crabs to find a house as they grow. The sea anemone settles on the snail shell that the hermit crab is living in, extending the size of the crab’s living space as it grows beyond the original diameter of the shell. Careful collection of the hermit crab and its sea anemone meant that the scientists who described the sea anemone were able to observe how it interacts with its hermit crab. This provided an unexpected glimpse into behaviors that normally happen more than a mile below the surface, and showed that the hermit crabs actively move their anemones with them if they change shells. The way that the hermit crabs bring their anemone along with them resembles the relationship between the sea anemone's namesake Calcifer and the wizard Howl in “Howl’s Moving Castle,” a fantasy novel by British author Diana Wynne Jones, later adapted by Hayao Miyazaki and the animation studio Studio Ghibli. The storybook Calcifer is a highly magical fallen star, bound to live in Howl's moving castle, just as the golden cloak anemone is bound to live on the moving shell of its hermit crab.

Original source: Yoshikawa, A.; Izumi, T.; Moritaki, T.; Kimura, T.; Yanagi, K. (2022). Carcinoecium-Forming Sea Anemone Stylobates calcifer sp. nov. (Cnidaria, Actiniaria, Actiniidae) from the Japanese Deep-Sea Floor: A Taxonomical Description with Its Ecological Observations. The Biological Bulletin. 242(2): 127-152., available online at https://doi.org/10.1086/719160

Satan's Mud Dragon (Leiocanthus satanicus)

Credit: Cepeda et al. (2022) (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Despite the imposing name this species is nothing to be feared. At only about half a millimeter long, mud dragons are small, segmented animals found in the mud or sand from shallow seas to the greatest ocean depths where they feed on small particles in the sediment. These unusual little animals belong to an entire phylum of their own: the Kinorhyncha. Mud dragons, or kinorhynchs, have an exoskeleton and are related to other animals that share an exoskeleton like arthropods, tardigrades, nematodes, and a less well-known phylum called Loricifera, which was only discovered in 1983!

This species was discovered in the Gulf of Mexico, near Mobile Alabama and New Orleans. It gets its name “satanicus” from the two curved horn-like extensions it has on the top of its head (most visible in the drawing on the right).

Original source: Cepeda, D.; Sánchez, N.; Sørensen, M. V.; Landers, S. C. (2022). Leiocanthus quinquenudus sp. nov. and L. satanicus sp. nov., two new species of pycnophyid Kinorhyncha (Allomalorhagida: Pycnophyidae) from the Gulf of Mexico. Zootaxa. 5093(3): 315-336., available online at https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.5093.3.3

Squidward's Sphyriid Copepod (Tripaphylus squidwardi)

Credit: Boxshall et al (2022) (left) and Carton et al. (2022) (right) (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

This worm-shaped parasite is a type of copepod. Copepods are small shrimp like crustaceans that are usually about the size and shape of a sesame seed, but this copepod has evolved a very different shape better suited for its bizarre parasitic lifestyle.

The copepod is named after the Spongebob character Squidward, in reference to its big round head that resembles Squidward’s. It has an elongate body about 2.5 cm in length and it uses its bulbous head to remain firmly embedded in its host, the Australian blackspot shark Carcharhinus coatesi. As a tiny larval stage, this parasite finds a shark and burrows its head into the shark’s throat near the gills and then transforms into an elongate body that remains dangling in the throat of the shark like a parasitic uvula (the dangling structure found in the back of your mouth at the top of your throat). With its head embedded and most of its body hanging free in the throat, it releases its eggs, presumably to exit via the gills rather than the long way out.

Original source: Boxshall, G. A.; Barton, D. P.; Kirke, A.; Zhu, X.; Johnson, G. (2022). Two new parasitic copepods of the family Sphyriidae (Copepoda: Siphonostomatoida) from Australian elasmobranchs. Systematic Parasitology. 99(6): 659-669., available online at https://doi.org/10.1007/s11230-022-10054-4

Falkor's Black Coral (Antipathes falkorae)

Credit: Horowitz et al. (2022) (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Falkor’s Black Coral, Antipathes falkorae, is remarkable for its skeletal complexity, having more knobs and bumps on its skeleton than any other black coral. It is also surprisingly well connected: although A. falkorae was described from 100m, it is closely related to shallow water black corals, suggesting evolutionary linkages across bathymetry that have not been seen in this group. The story of its discovery is equally remarkable. The Schmidt Ocean Institute’s R/V Falkor was based in Australia during 2020, and was able to organize an expedition to bring scientists to the field despite the challenges of travel during the pandemic. Antipathes falkorae and the other new species and records obtained during the expedition provide details about diversity and geographic range necessary for understanding and making informed decisions about marine ecosystems.

Original source: Horowitz, J.; Opresko, D.; Molodtsova, T. N.; Molodtsova, T. N.; Beaman, R. J.; Cowman, P. F.; Bridge, T. C. (2022). Five new species of black coral (Anthozoa; Antipatharia) from the Great Barrier Reef and Coral Sea, Australia. Zootaxa. 5213(1): 1-35., available online at https://www.mapress.com/zt/article/view/zootaxa.5213.1.1

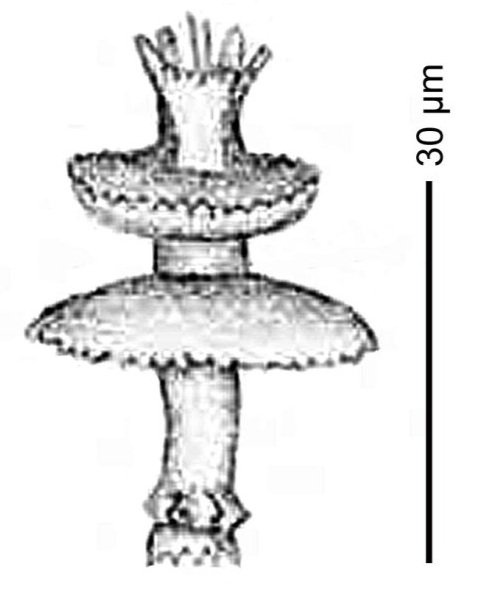

Ballerina Sponge (Latrunculia (Latrunculia) tutu)

Credit: Sim-Smith et al. (2022) (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

An international team of scientists has discovered a 35 million year old ballerina, or, at least, a sponge microskeleton that looks like one! In their study of the diversity of marine sponges, Kelly and Sim-Smith describe a new species, Latrunculia (Latrunculia) tutu, based on microscopic skeletal fragments recovered from deposits on the South Island of New Zealand. The tiny spicules, which give the sponge animal support and structure, are smaller than the width of a human hair. High-powered microscopes revealed that these spicules have a pair of whorls around their middle that look like the bodice and skirt of a ballerina and a small ring of spines at the top that resemble a crown. Although the ballerina sponge is known only from fossil deposits in the South Island of New Zealand, many similar species can be found alive and well in New Zealand and Antarctica. Although the fragmentary fossils of the ballerina sponge do not allow us much insight into these animals, living members of this group are colorful, ranging from green to turquoise blue to purple or brown, and some have proven to be interesting sources of biochemicals, including molecules with anticancer and antimicrobial properties.

Original source: Sim-Smith, C.; Janussen, D.; Ríos, P.; Macpherson, D.; Kelly, M. (2022). The Marine Biota of New Zealand: A review of New Zealand and Antarctic latrunculid sponges with new taxa and new systematic arrangements within family Latrunculiidae (Demospongiae, Poecilosclerida). NIWA Biodiversity Memoir. 134: 1-144.

Reynolds' Deep-Sea Crown Jelly (Atolla reynoldsi )

Credit: Matsumoto et al. (2022) (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Made you look! The absence of a long and trailing tentacle in these deep-sea crown jellyfish viewed on video collected by remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) deployed by the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) prompted scientists to collect and examine these animals more closely. A study of more than 30 individuals collected from Monterey Bay over a ten-year span determined that rather than the result of injury or of individual variation, this missing tentacle is part of the evidence used to identify this of a new species, named Atolla reynoldsi after the first volunteer at MBARI’s education and conservation partner, the Monterey Bay Aquarium. The authors found that samples of the deep red jellies that lacked the trailing tentacle are genetically distinct from the ten known species of Atolla, with a handful of additional anatomical differences visible when the animals are viewed up close and personal. Although it settled the question of the meaning of the missing tentacle, the deep dive into diversity in these deep-sea crown jellies provided by the description of A. reynoldsi revealed gaps in knowledge of this lineage of jellyfish, including additional (as yet unnamed) species.

Original source: Matsumoto, G. I.; Christianson, L. M.; Robison, B. H.; Haddock, S. H. D.; Johnson, S. B. (2022). Atolla reynoldsi sp. nov. (Cnidaria, Scyphozoa, Coronatae, Atollidae): A New Species of Coronate Scyphozoan Found in the Eastern North Pacific Ocean. Animals. 12(6): 742., available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2076-2615/12/6/742

How were the species chosen?

A call for nominations was announced in December 2022, sent to all editors of WoRMS and editors of major taxonomy journals, and posted openly on the WoRMS website and social media so anyone had the opportunity to nominate their favorite marine species. Nominated species must have been described between January 1st and December 31st, 2022, and have come from the marine environment (including fossil taxa).

A small committee of volunteers (including both taxonomists and data managers) was brought together to decide upon the final candidates. The list is in no hierarchical order. The final decisions reflect the immense diversity of animal groups in the marine environment (including crustaceans, corals, sponges, jellies and worms) and highlight some of the challenges facing the marine environment today. The final candidates also feature some particularly astonishing marine creatures, notable for their interest to both science and the public.

The views and opinions expressed by guest contributors do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Ocean Oculus.